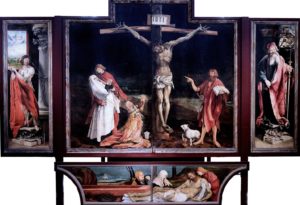

This devotion is a little bit different than the rest. Instead of a single scripture passage from which to work and meditate, above you will find Matthias Grünewald’s “Isenheim Altarpiece.” Though designed by a German, this piece of stunning artwork presently resides at the Unterlinden Museum at Colmar, Alsace, in France (a reflection of many European wars that have blended German and French culture and cultural artifacts). I would encourage you to read all about this piece on Wikipedia because what you’re seeing above is just one of three images present as the altarpiece is altered (if you’ll forgive that pun!) by opening and closing different wings.

I’m sharing this here, though, for our devotional reflections because Grünewald has provided us a meaningful interpretation on John the Baptist and it is John the Baptist’s life that we’ll be focusing on throughout all of Advent. And so, ultimately, this midweek devotion is meant to introduce you to Advent, which begins this Sunday.

Who gets to interpret scripture is an interesting question. Biblical scholars? Sure! Translators? By default! Pastors in the pulpit? Such are the terrifying duties of that calling. What about artists? Do they get to interpret scripture? Well, Grünewald seems to answer this question in the affirmative as he provides us a remarkable interpretation of the ministries of both Jesus and John.

As for Jesus, if you look closely, you’ll see that He is covered in sores and lesions of various sorts. That’s because this piece was painted for the Monastery of St. Anthony in Issenheim near Colmar, which specialized in hospital work. According to Wikipedia, “The Antonine monks of the monastery were noted for their care of plague sufferers as well as their treatment of skin diseases, such as ergotism. The image of the crucified Christ is pitted with plague-type sores, showing patients that Jesus understood and shared their afflictions.”

That’s a remarkable interpretation by Grünewald, for what do we hope for in the midst of our own afflictions other than that we won’t be alone in them? How much better, then, that not only do we find ourselves met in our afflictions, but met by none other than the Christ of the world! Grünewald would not have you believe for even one second that whatever it is that ails you is your burden to carry alone. No, as he shows us, Christ carries that burden – carrying it even to the Cross. In this, we remember that whatever our burdens, they meet their end in the cross, for in the resurrection – both Jesus’ and our future resurrections – these afflictions do not continue with us. Such is the profound hope of this artistic interpretation of scripture.

But now to John the Baptist, who represents for us the best of Christian discipleship, especially in Grünewald’s hands. For in Grünewald’s hands, we have to ignore the anachronistic nature of this painting (that is, John is beheaded long before Jesus is crucified, therefore he couldn’t be witness to the crucifixion), but if we do so, we learn something about ourselves. And what is that?

First, we learn that we are not at the center of our own lives. John the Baptist is “decentered” (side note: “Decentering” is a theme to which we’ll return during Lent 2022!). John does not need the spotlight because he knows that his life is better lived in the light that Jesus shines – and that Jesus’ light never shines brighter than when we put Christ at the center of our lives.

Second, we learn that our lives – like John is doing in this painting – are best spent pointing away from ourselves and toward the Christ. This is why our Advent series is titled “The Pointing Prophet.” It’s because John is the last of the Old Testament prophets who point to the coming Christ. (Side note #2: Maybe Grünewald’s anachronism of having John at the cross is a reflection of another anachronism – that is, John the Baptist is an Old Testament prophet who only appears in the New Testament!).

Now, I know that all of our mothers taught us “don’t point.” We might have even been told during our lives that “when you point one finger at another, three more are pointed back at you.” And that’s all good enough advice for how to live faithfully and gently with one another. However, when it comes to your life and my life, the best any of us can ever do is point others toward the Christ. The way Grünewald presents John puts us into an almost endless, cyclical loop in which our eye strays to see John, who then leads us back to Jesus, until our eye strays back to John, who then (again!) points us back to Jesus. And so on and so on and so on.

Third, if you look very closely above (or find other versions of this altarpiece online), you will see that between John’s pointing finger and his face is a Latin phrase – “illum oportet crescere me autem minui.” This comes from the Latin Vulgate translation of the Bible, John 3:30, which is John the Baptist’s most famous line: “He must increase, but I must decrease.” A life of authentic Christian discipleship finds ever-new ways to decrease its own self-importance in favor of the importance of Jesus’ life, mission, and ministry in the world. Indeed, even the act of pointing away from one’s self (especially in a world in which every person is tempted to cultivate their own “brand”) is a way of decreasing the self and increasing the Christ. When this is paired with his “decentered” position in the artwork, the message rings all the louder and all the clearer.

So, friends, I invite you to spend time focusing on this piece of art and to attending all four weeks of Advent so that we might all learn together what it means to become “pointing prophets” of the coming Christ. Amen.